The Chameleon: What Being Asian American Means to Me

Growing up I always felt like a chameleon: blending into the race of the majority of my friends. I didn’t realize the gravity of what that meant and what that said about my identity until I was hired at Intertrend, an advertising agency that specializes in speaking to an Asian American audience.

Intertrend prides itself in helping companies navigate the cultural nuances of different Asian ethnicities from Chinese to Asian Indian, and even harder to reach markets, such as Hmong or Cambodian. Coming out of college and entering the workforce, I didn’t even realize that companies had specific marketing strategies dependent on ethnicity. Discovering the work Intertrend does made me realize that my voice as an Asian American is important and valued. However, finding my voice and being proud of my cultural heritage has been a long journey for me.

I grew up in Lomita, CA a small town in the middle of the South Bay between San Pedro, Torrance, Palos Verdes, Redondo Beach, and Harbor City. All of those places are more commonly known and perceived in specific ways, so growing up in a small town like Lomita, that really didn’t have an identity of its own, pushed me to spend most of my time in cities that did. Consequently, I looked elsewhere for a sense of community, culture, and belonging.

I always wound up being the token Asian in my group of friends because I always felt weird hanging out with a group of solely Asians. I felt more comfortable hanging out with people of any race other than my own. I told everyone that I was half white and half Asian because my stepdad since I was 2 years old is white and I have a birthmark in my hair that is a blonde streak. I would use these two reasons to justify that I was “hapa.” If I couldn’t be fully white, then at least half would do.

As fate would have it, I was in my second to last semester of college and studying abroad in Madrid, Spain. Most of my other peers already had internships and jobs lined up for the summer. However, as I was studying abroad and traveling almost every week, I had procrastinated on this task.

At the last minute, I found Intertrend through USC’s career site, and the date of their internship program lined up perfectly with my return to Los Angeles. I quickly reviewed their website and social accounts, and thought it would be a fun place to work at. At the time, I didn’t even internalize the importance of the fact that they focused on multicultural advertising in the Asian American space. On a whim, I decided to apply and was accepted.

It wasn’t until I started working at Intertrend that I made a conscious realization: I never wanted to hang out in purely Asian circles due to what “other” people might think. I didn’t want “other” people thinking that I was the stereotypical unassimilated FOB (Fresh Off the Boat) or “chink.” I didn’t want to be seen as part of that group.

I never wanted to hang out in purely Asian circles due to what “other” people might think.

I always tried so hard to fight the typical stereotypes that Asians are smart, quiet, compliant, model minorities. Thus, I was always loud, tried to be the class clown, tried to hide how smart I really was, and always wound up in trouble. I never wanted to be labeled as “Asian” because I wanted to be seen as part of another group. I wanted to be seen as cool and popular the way mainstream media portrayed Anglo protagonists.

In her article, Finding Asian Identity in a Black and White America, Eda Yu writes that being Asian American is to be “defined by liminality — always positioned in reference to another, more dominant culture; it rarely feels distinct and coherent enough to stand alone.” This is why I acted like a chameleon for much of my life, figuring out my own identity in relation to other more dominant cultures.

Being Asian American is to be “…defined by liminality — always positioned in reference to another, more dominant culture; it rarely feels distinct and coherent enough to stand alone.” — Eda Yu

And this is why diverse advertising and the work we do at Intertrend is so important. Our Asian American cultures are just as unique and enriching as the next. Our cultures are just as important as any other. No culture should be dominant. Diverse advertising acknowledges this point and tells consumers that their culture is just as valuable as mainstream Anglo America. From a business and client standpoint, this also leads to more sales and revenue because our campaigns are based on strategic cultural insights. Even though the advertisements may be executed on a larger scale, we are speaking to the consumer one on one. Jeff Goodby and Rich Silverstein from the advertising agency Goodby, Silverstein & Partners, coined the term “mass intimacy” to describe this strategy.

For brands to talk to consumers on an intimate level, they must first understand the cultural nuances between different ethnicities and groups. For example, the way you communicate to a first generation Chinese immigrant in their 50s will be intrinsically different from how you connect with a third generation Korean-American in their 20s. As an Account Executive, my job at Intertrend is to educate brands and our clients on these nuances. From there, Intertrend leverages these nuances to create campaigns that truly resonate with our target audiences.

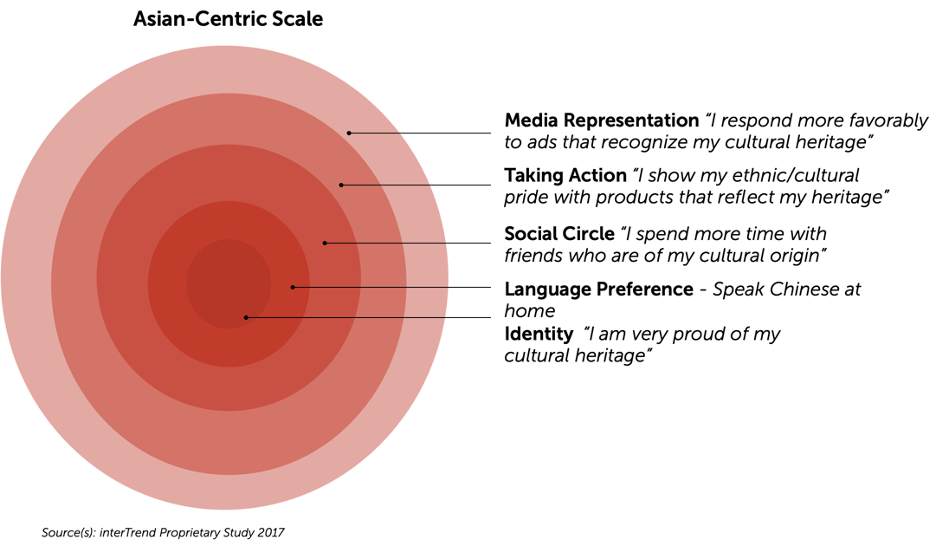

When I started working at Intertrend and learning about their process, I realized how truly important one’s cultural heritage is. As a 1.5 generation Asian American, I realized that I didn’t have to choose between being Asian or being American. I could create and live in a unique space along with other 1.5–2nd generation Asian Americans, pulling elements from both that best expressed our unique experience. Intertrend coined the term Asian Centricity, “the way in which Asian culture, beliefs, values, and/or traditions dictate and influence one’s identity, attitudes and behaviors, including language preference, social circle, entertainment choices, and media consumption.” I could be both highly acculturated and Asian centric. They didn’t have to be mutually exclusive.

Growing up, I never saw advertisements or mainstream media that truly resonated with me. Consequently, this is why I tried so hard to be a part of mainstream white America. Intertrend helped me to understand that my unique culture and experiences are just as important. It gives me the opportunity to educate brands and clients on why the work that we do is so important in connecting with consumers and, ultimately, their bottom line. Having been at this job for four years now, I can see how my work has amplified my ability to find my voice as an Asian American, so that I can now better help others find that voice for themselves. I am proud to no longer have to change the color of my outward appearance, and I hope to inspire the same for others. This chameleon is staying yellow, no matter the environment.