Patience School - Lessons From the Tiger Parenting Resistant

Managing the Gravitational Pull of Asian DNA v. Wholehearted Parenting

Harmonious Perseverance

Parenting is tremendously hard work. I feel responsible not only for the survival of these little beings, but also for molding them into contributing members of society who achieve their highest potential. What I have learned is that parenting is not just about the children and their needs, but also about self-discovery along the way. I wrestle with my demons that have emerged during this process. While I want my kids to live up to their full capacity accountable to my high expectations, I also want them to be self-motivated and strive for what they want out of life. At the same time, I also want them to soak in many gratifying life experiences, while I enjoy some of the fun family moments with them as a parent.

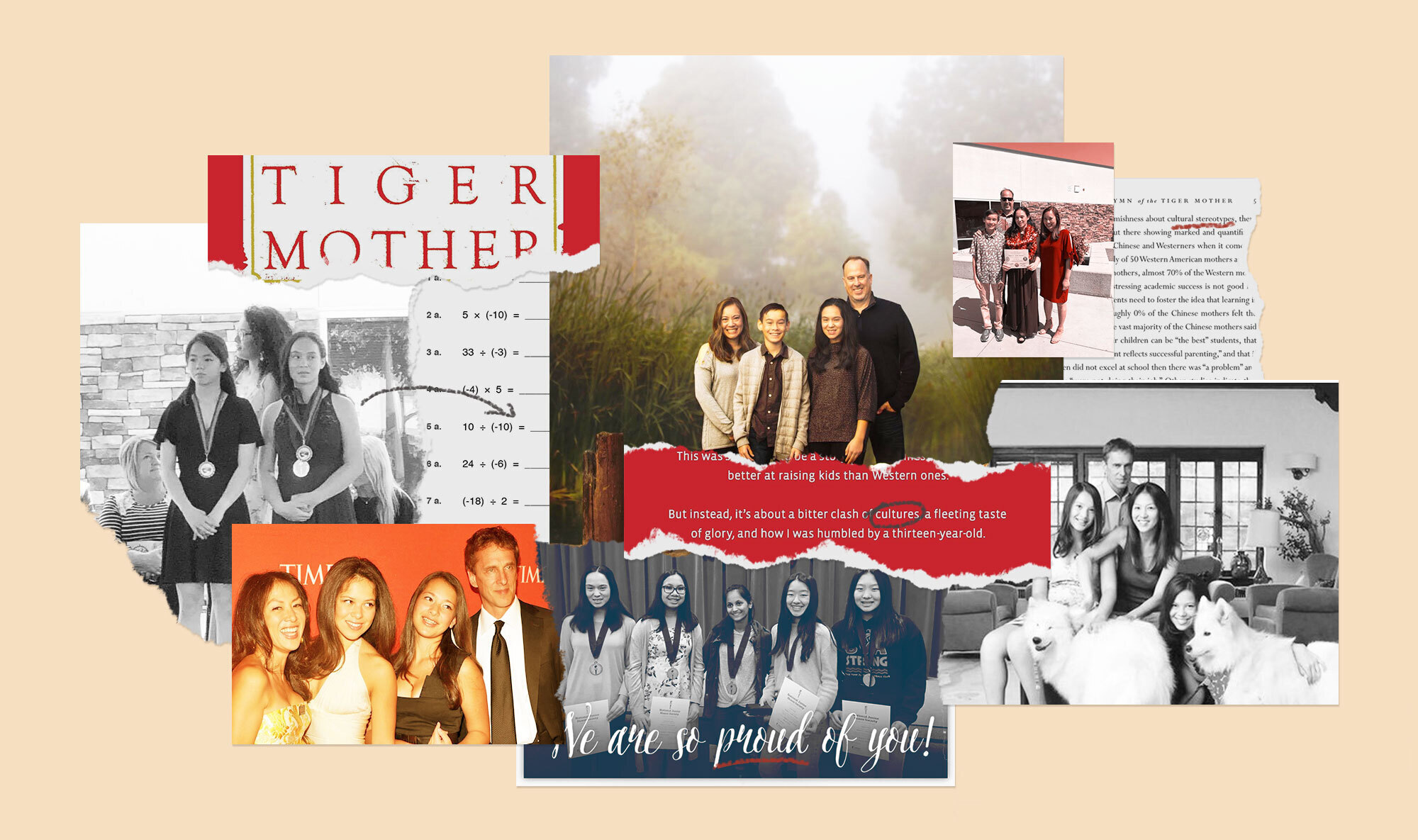

Amy Chua’s satirical memoir, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, is a comparison of Chinese and Western parenting philosophies that polarized readers and resulted in significant controversy. Many view her parenting style as extremist in nature, with strict rules such as never once allowing her kids to attend sleepovers, get any grade less than an A, and fail to come first in any class except gym and drama. Amy tells stories of how she rejected handmade birthday cards from her daughter because she deserved better and more effort, or calling her garbage in other situations.

As a third and fourth generation Chinese American with two hapa teenagers, I often think of myself as carefully balancing the two parenting styles. While reading Battle Hymn, I could see positive merits to both ideologies. The challenge is how to delicately nurture a harmonious intersection during this ever-constant quest for self-improvement in the world of parenting.

The Labels

For a colleague’s baby shower, I created a quiz with the question, “What type of parenting style do you think the mother- and father-to-be will adopt?” There were fun answers like: Lawnmower Parent, Helicopter Parent, Free-range Parent, Attachment Parent, Tiger Parent, and Elephant Parent. Parenting labels have been the rage, with infinite analyses and articles attempting to triangulate the archetypes and bring awareness to the hyper-involved, over-protective hallmark parent profiles. But ultimately, labels provide opportunities to place judgement on other parents, when society should instead provide guidance on how to use intuition to solve problems and guide unique circumstances.

I remember an instance of my own “Helicopter” parenting that I am reluctant to admit. It was 11pm on a Thursday night and I glanced over my daughter’s sixth grade math homework. 100% of it was wrong. Exasperated and exhausted, I didn’t have the energy to teach her, but I also couldn’t let her hand in incorrect homework because that would be unbearably embarrassing for her and for me. So, what did I do? I proceeded to do all of the problems for her to copy and turn in! That Saturday, we sat down and went over it until she mastered the concept. This memory is something that I am ashamed to fess up to because I am well aware that this type of behavior does not do our children any favors. After reading so much literature such as Wendy Mogel’s The Blessings of a Skinned Knee and The Blessings of a B Minus, I know that kids need to experience failure to grow up with a healthy, self-reliant mindset.

Mostly, my Caucasian husband has labeled me a Tiger Mother. While I sometimes blame my genes when it’s convenient, I do believe that my Asian DNA is embedded somehow and there are innate drivers and philosophies that are part of my heritage.

Lessons From the Ultimate Tiger Mother

“The Tiger, the living symbol of strength and power, generally inspires fear and respect.”

Amy Chua seems to unwaveringly believe that Chinese parents are better at raising kids than Western ones (at least towards the beginning of her journey in the book). She explains that:

Chinese parents have two things over their Western counterparts: 1) higher dreams for their children, 2) higher regard for their children in the sense of knowing how much they can take. Chinese parents demand perfect grades because they believe that their child can get them. If their child doesn’t get them, the Chinese parent assumes it’s because the child didn’t work hard enough. That’s why the solution to substandard performance is always to excoriate, punish, and shame the child. The Chinese parent believes that their child will be strong enough to take the shaming and to improve from it. Second, Chinese parents believe that their kids owe them everything. Third, Chinese parents believe that they know what is best for their children and therefore override all of their children’s own desires and preferences. It’s not that they don’t care about their children. Just the opposite. They would give up anything for their children. It’s just an entirely different parenting style.

Amy talks about extreme threats she had made, “If next time’s not perfect, I’m going to take all of your stuffed animals and burn them!” Amy would attempt to make up after the fact by leaving little notes for them everywhere — on their pillow, in their lunch boxes, saying things like, “Mommy has a bad temper, but Mommy loves you!” I cringed when I read this, because I have similarly offered these post blow-ups, guilt-ridden sweet apologies. At the same time, I also feel comforted that I’m not alone in this.

I know that I can also be wickedly cruel in fits of Tiger Parent-like frustration, but then I also try to inspire and motivate my children with positive reinforcement. It can be agonizing all the while, being pulled into two directions.

I am not a Tiger Parent because… my kids were allowed to have playdates and sleepovers throughout their upbringing.

I am a Tiger Parent because… I check the standardized testing schedule and won’t allow sleepovers or campouts within two weeks of this.

I am not a Tiger parent because… I allowed us to go on family ski trips.

I am a Tiger Parent because…. I packed standardized test prep workbooks for some productive non-screen time in the long road trips to ski destinations.

You Are Your Report Card

When my daughter was in kindergarten, they had a daily writing journal. I remember coming home from work one day and reviewing her journal; I could tell it was hastily written in a sloppy manner. So, I ripped out the pages and made her re-do it. While I could tell she was upset with my reaction, I wanted to show her that she had to have pride in her work. Even as a kindergartner, she was to focus effort into each assignment, and this discipline would result in better grades as she got older.

I remember a text from my daughter when she was in the first few years of elementary school, it coldly said, “I got an A, so are you happy now?” It was such an oddly toned text, but it made me think about whether I was overemphasizing grades. In reality, I resonate with Amy Chua on this topic because I push my kids to get better grades because I know they are capable.

My daughter is now in her first year of high school, an uber competitive one, with a ridiculous schedule packed with an intense season of high school volleyball, year-round club volleyball, playing piano on track for a certificate of merit, and dance. The semester started out a little shaky during the transition from middle school, but I watched her work her tail off to claw back and attain a 4.6 GPA. I am very proud of her for accomplishing this and having the grit to push forward. I would like to think that the years of slowly guiding and pushing her have contributed to this.

I have explained to her that effort itself is valuable, that if I’m choosing between hiring two candidates at work, I would choose the person who has a great attitude and work ethic over solely finding the smartest candidate. And my daughter has intense focus, determination, self-discipline, thoughtfulness, and kindheartedness that will be big contributors. Then again, I have also advised her to use the first few tests in a class to learn what the teacher expects and wants, in order to “crack the formula” for getting the grade. In other instances, I have coached her to do “just enough” for the A in classes where it’s a given, while allocating her limited time towards the classes that require more. I feel conflicted because I know that we should not be solely focused on grades and test results, and we should always encourage the pure joy and love in learning, but that seems like a utopian world. I know that the world is competitive, getting into college is challenging, and one ticket to financial success and stability is a strong education. On one side, I do need her to get into college. Yet, I need to remind myself that the whole person is more than a report card.

Spying On the Competition

Amy seems hell-bent on pushing her kids to the extreme, to be “the best.”

She summarizes:

A Chinese mother believes that 1) schoolwork always comes first, 2) an A- is a bad grade, 3) your children must be two years ahead of their classmates in math, 4) you must never compliment your children in public, 5) If your child ever disagrees with a teacher or coach, you must always take the side of the teacher or coach, 6) the only activities your children should be permitted to do are those in which they can eventually win a medal, 7) and the medal must be gold. Chinese mothers said that they believe their children can be “the best” students, that “academic achievement reflects successful parenting.”

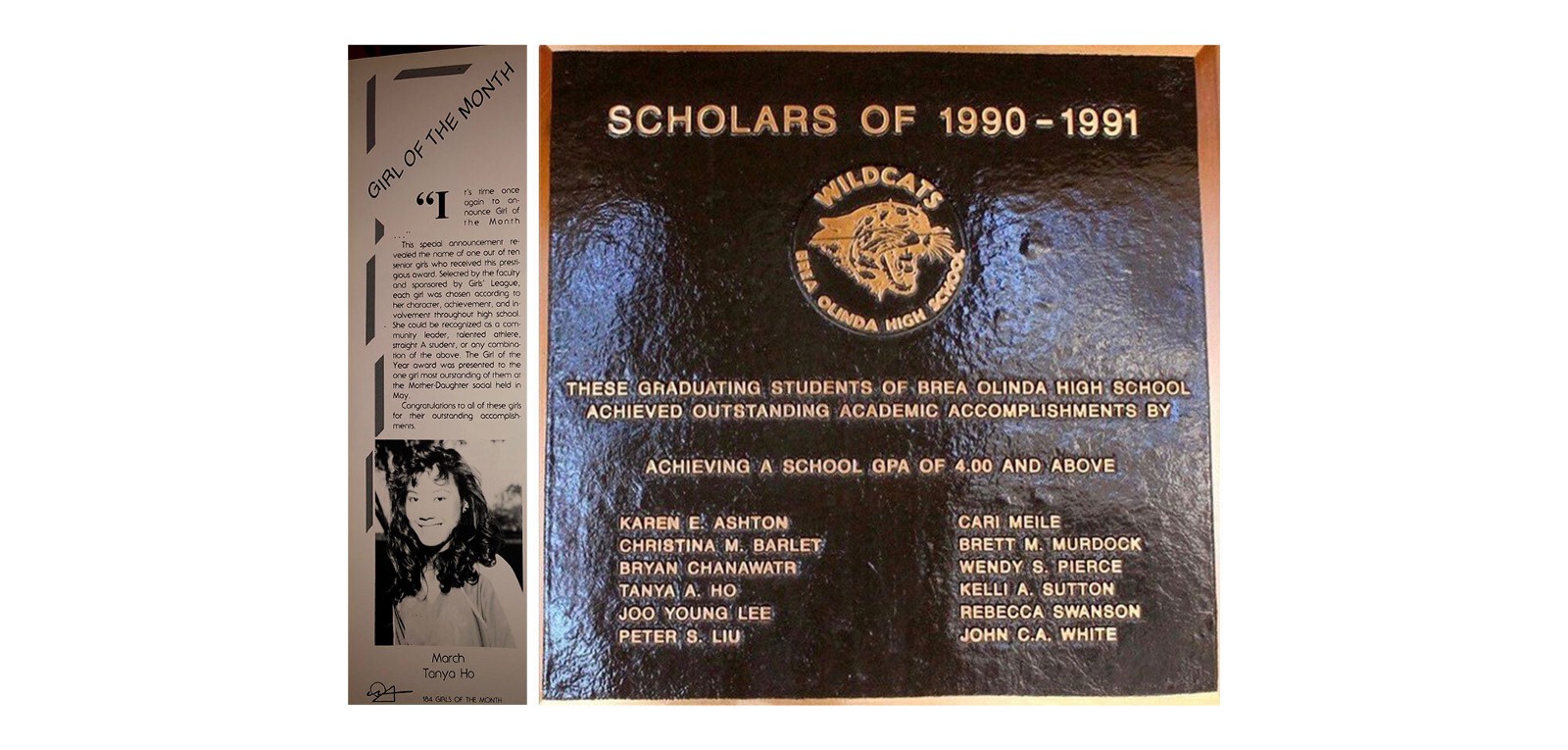

I’m not sure if competitiveness is innate or developed. For me, I always cared about how I was doing compared to my peer group, particularly in school. I distinctly remember constantly wanting to be number one to finish assignments in first grade and hurrying to turn them in, so much so that it was mentioned in a parent conference that I was unnecessarily rushing through things. At the age of six or seven, I reviewed future pages of a standardized test in advance and saw multiplication, which I hadn’t learned yet. That night, I vividly remember how I asked my parents to teach me, sitting on their bed as they broke it down, “Think of it as 2 sets of 3 equals 6.” My self-motivated desire to perform well turned into a strong internal sense of competition as I grew older. If my friend or peer received a 97, I desperately and achingly wanted to score at least a 98, although externally I would act as if it didn’t matter at all.

Thus, I was quite perplexed when my kids did not turn out to share my instinctive sensibility. I recall asking my daughter how she did on a test when she was in kindergarten or first grade. I proceeded to ask how the class did in comparison. She didn’t know. “How about your tablemates? Your friends?” She had absolutely no idea. Incredulous, I demanded, “Well, why not?” I think my constant probing had an impact, because one day she proudly announced, “Today, I went to sharpen my pencil and I was able to see people’s scores,” promptly reporting them back to me like a spy. My children would volunteer to be the class “paper passer” for the same reason, doing the important job of handing back graded papers with an ulterior motive.

While I admit that this is not wonderful modeling, competition can be both positive and negative. On the downside, constantly comparing your kids to others can be harmful, and I certainly don’t want them to be annoyingly in peer’s faces about keeping scorecards. But a sense of competition can be a beneficial and healthy motivator as well, pushing them to do their personal best.

Asian Values: Education is the Lifeline

Growing up in a near 100% White suburb of Denver, my kids have a completely different experience than I had in school. We now live in a majority Korean neighborhood in Orange County. The elementary school is 85% Asian and the high school is 46% Asian.

Living in this environment today has it positives and negatives. I believe that the high percentage of Asian families correlates to affluence, test scores, and real estate values (Chalkbeat analysis and GreatSchools report). In general, I have observed the Asian cohorts in my neighborhood being extremely attuned to their kids’ performances in school and doing whatever it takes to give their superstar honors gifted kids an edge. This often means Kumon programs and tutoring networks. Weekend Chinese or Korean school. Taking the SATs in middle school. Taking college level Calculus as a junior in high school. We are one of the few families that have not engaged in tutoring, although my daughter is maintaining pace with those kids on her own merit. This frenzy produces an environment of pressure for both the kids and parents alike. I find myself judging the crazy Asian parents, giving myself permission to call them that because I am one myself, although with different priorities. Seeing these parents trying to do everything in their power to set their kids up for success is admirable. But it provides a boundary of where I will not venture.

Similarly, Amy’s perspective is heavily focused on academics, with a total ban on TV-watching, playdates, and sleepovers. And she dictated which musical instruments her children must play (only piano and violin were acceptable), forcing them to practice no less than six hours per day, even on international vacations.

Amy’s perspective is as extreme as expected:

I wanted her to be well rounded and to have hobbies and activities. Not just any activity, like “crafts,” which can lead nowhere – or even worse, playing the drums, which leads to drugs – but rather a hobby that was meaningful and highly difficult with the potential for depth and virtuosity

Because I am not the daughter of immigrants (my parents are children/grandchildren of immigrants), my parents were not typical Asian parents. Ironically, I don’t remember them putting any pressure on me whatsoever. With underlying assumption and trust that I would do well in school, they let me have a great deal of freedom to endlessly play, use my imagination, and have sleepovers. I recall having friends over in elementary school, and we would create mock magazines (writing faux articles), playing school, creating faux tests and lesson plans, and making up game shows, using our creativity to the fullest. Though they did take me to the library often, they also allowed me to play Atari and the Apple IIe computer to my heart’s content, watch soap operas, and go skiing often.

I feel that it is important to deliberately infuse more balance and allow my kids to learn from varied sources of life. For example, I let our kids choose their own extracurriculars like Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. What started as Mommy and Me ballet for one, led to both of them playing soccer and piano, and, more recently, years of baseball, karate and lacrosse for him, and ballet, contemporary, and club volleyball for her. When they were younger, I signed them up for all kinds of enrichment camps — science camp, coding camp, creative writing camp, design camp, Minecraft and Roblox camp. My non-Asian in me even signed them up for the art camp and sports camp. That made me feel a little bit rebellious, like I was countering the typical Asian sentiment and promoting creative innovation with art and leadership skills with sports.

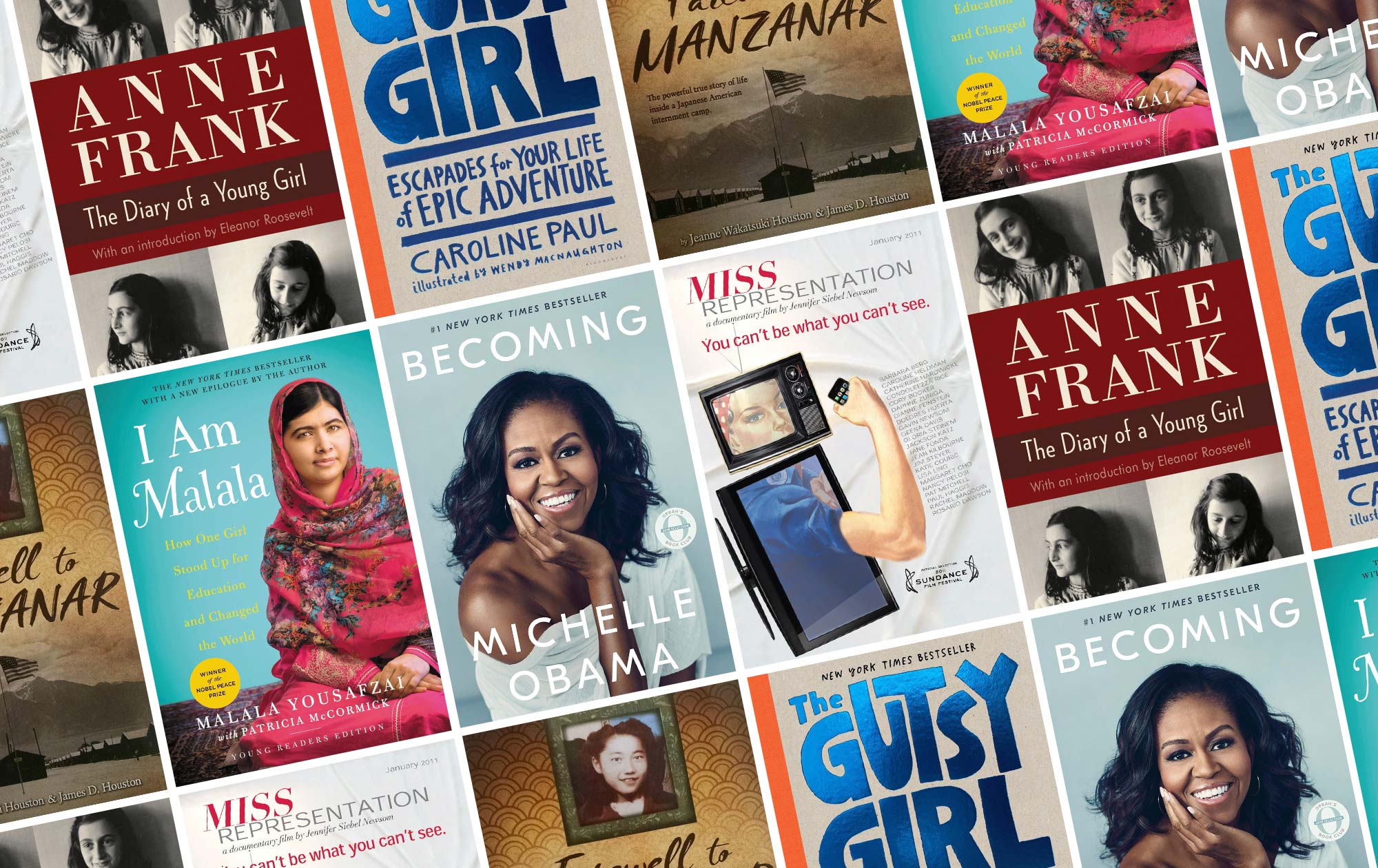

What I find myself doing is demanding a great deal as well, but a holistic set of influences instead: academic, extracurricular, and also cultural enrichment. I made them both listen to entrepreneur podcasts like those hosted by Guy Raz, TED Talks, and Greta Thunberg speeches. I made them read Diary of Anne Frank, I Am Malala, and Farewell to Manzanar. I had my daughter read Gutsy Girl, Michelle Obama’s Becoming, and watch Miss Representation. They spent 30+ hours each year crafting a self-produced team movie to consistently earn 1st or 2nd place in their school’s annual film festival, one time showcasing the founding of a non-profit organization that welcomes refugees to the communities.

The overwhelming drive around us towards one dimensional academic success motivates me to approach things differently, making sure they also have a global view of issues and justice. In the big picture, I hope this fits into the whole college application personal story. So, it is ultimately a balance of personal growth and enrichment, but also a means to an end.

Patience School

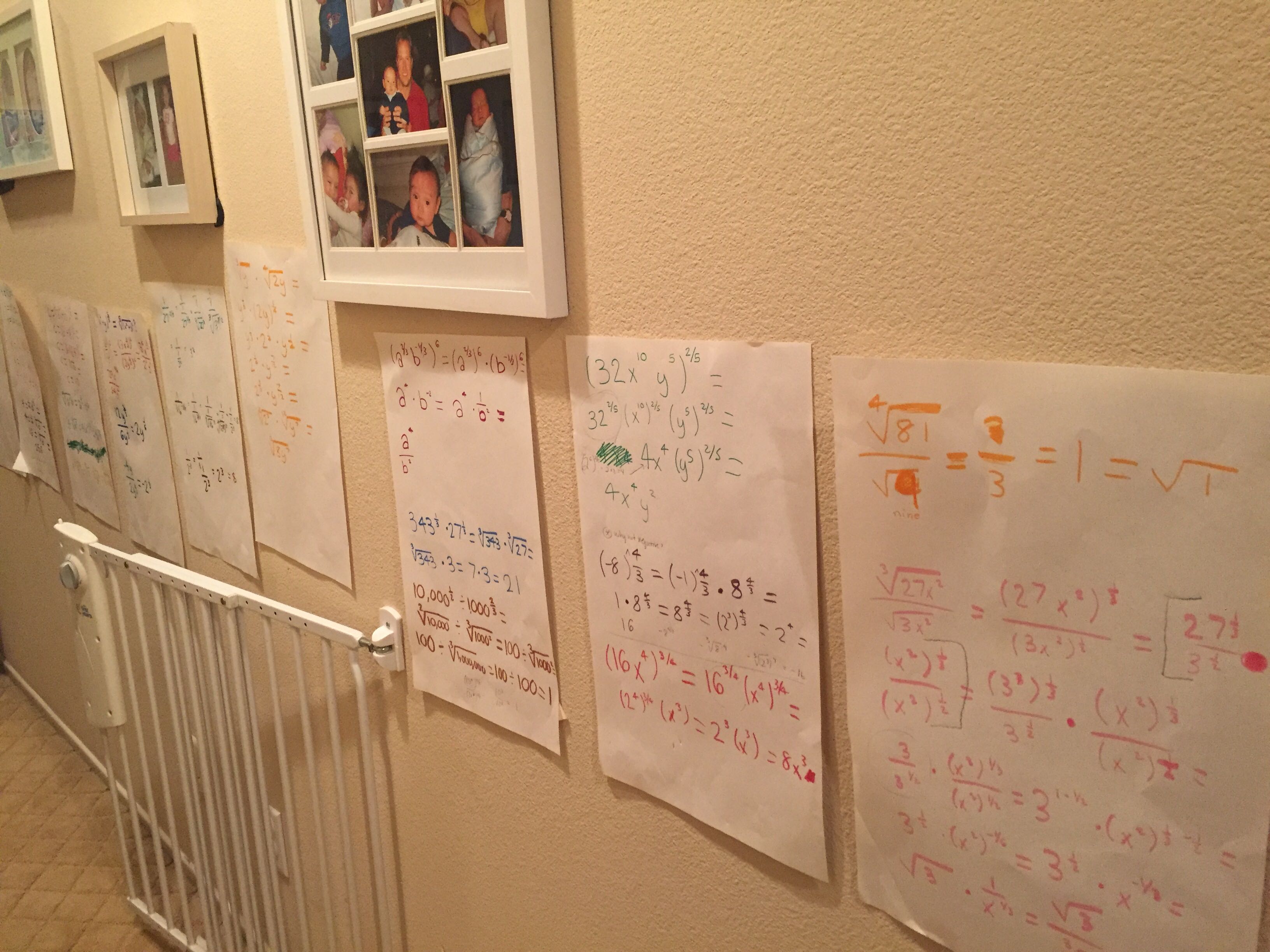

Amidst the tutoring frenzy among Asian parents, I decided that I didn’t want to spend money on tutoring my honors kids and that I didn’t have the time to add that to their schedule. However, I did say, “Congratulations! For your 7th grade algebra and 8th grade geometry, I will be your tutor!” There is a reason I never considered being a teacher — I know my strengths and patience is not one of them. Countless episodes of tears later, my daughter boldly states, “You need to go to patience school.” I don’t disagree.

Each time, I begin with good intentions, starting with deep breaths and a kind, “How can I help you?” Then my daughter doesn’t understand something and things spiral. Frustrated, I start thinking to myself (and hopefully never out loud), “What the hell is wrong with you? Why aren’t you getting this most basic concept? Why are you making stupid mistakes?” We go to bed angry and giving each other the silent treatment. The next morning I write her apologetic texts and emails. My husband (As the teacher in the family, why doesn’t he just do the tutoring?) would try to smooth things over.

I couldn’t bring myself to drag the kids to tutors when they are doing well. It crosses the line. Making the decision to forfeit the outside tutors and bravely DIY-ing on a la carte help was a deliberate one. I adore math, minored in math in college, and believe that it’s incredibly fun. Part of me wanted to be able to bond with my daughter in this. The risk was to damage our family fabric.

Amy reflects on this and says, “I wouldn’t wish myself on anyone. There’s been a lot of yelling and screaming in this house. To tell you the truth, it’s been traumatic.” She has friends who compliment, “But you’ve given your girls so much… a sense of their own abilities, of the value of excellence. That’s something they’ll have all their lives.” I can only hope that this is how my children will feel someday.

Hands Free Mama

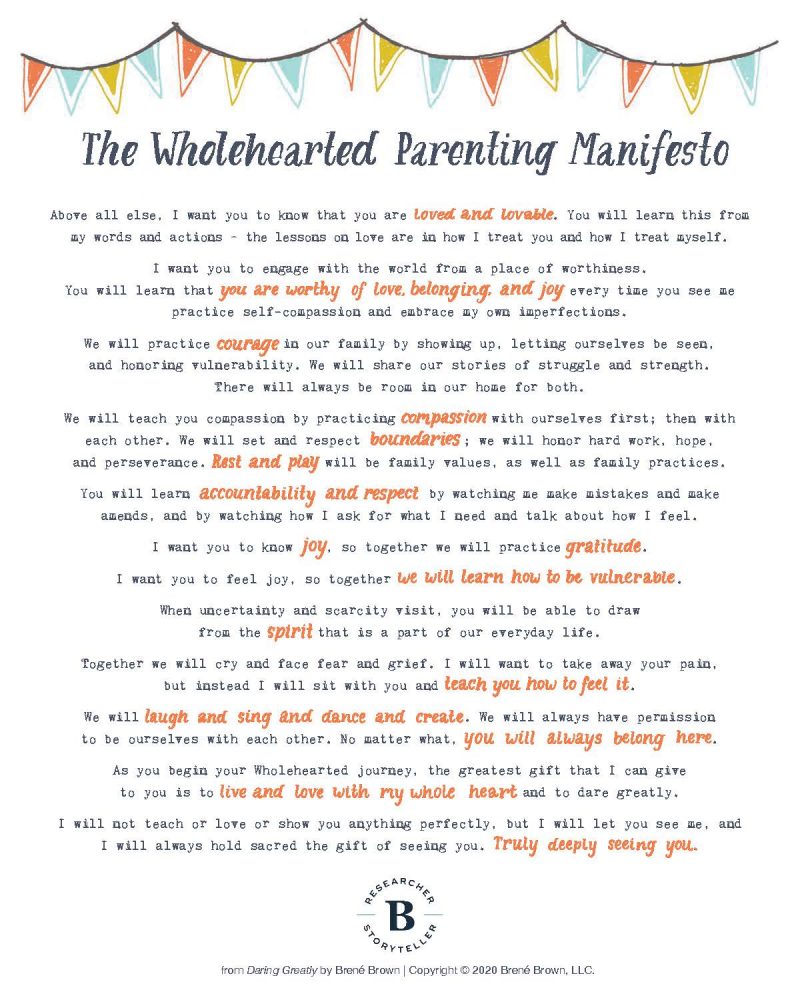

I am a fan of Brene Brown, whose famous TED talks and books about vulnerability, shame, and empathy are fascinating. Brene Brown’s parenting approach seems a one hundred eighty degree turn from Amy Chua’s philosophy. Brene emphasizes an expressive declaration of love first and foremost and an acceptance of struggles, and Amy talks about strict enforcement of achievement above all.

She has something I’ve downloaded called the Wholehearted Parenting Manifesto. Here is an excerpt:

- Above all else, I want you to know that you are loved and lovable. You will learn this from my words and actions - the lessons on love are in how I treat you and how I treat myself.

- I want you to engage with the world from a place of worthiness. You will learn that you are worthy of love, belonging, and joy every time you see me practice self-compassion and embrace my own imperfections.

- We will practice courage in our family by showing up, letting ourselves be seen, and honoring vulnerability. We will share our stories of struggle and strength. There will always be room in our home for both.

Ok, Brene Brown. There you go exposing my parenting vulnerabilities, leading to my guilt and shame about not being a better positive parent. Everything here makes perfect sense, but it is more touchy-feely than how I approach things. I’ve told my kids on occasion that, “When I yell at you, that is my way of showing how much I care. Because if I didn’t care and love you, then I wouldn’t be here.” I do think that we arrive at the same place, and I know my kids know that they are worthy and loved. I can work on demonstrating that worthiness of love does not equate to accomplishments. And that’s why I bookmark this. It’s a constant quest for betterment.

Another reference for me is a TED Talk by Julie Lythcott-Haims, Dean of Freshman at Stanford:

What I'm saying is, when we treat grades and scores and accolades and awards as the purpose of childhood, all in furtherance of some hoped-for admission to a tiny number of colleges or entrance to a small number of careers, that that's too narrow a definition of success for our kids. And even though we might help them achieve some short-term wins by overhelping — like they get a better grade if we help them do their homework, they might end up with a longer childhood résumé when we help — what I'm saying is that all of this comes at a long-term cost to their sense of self. What I'm saying is, we should be less concerned with the specific set of colleges they might be able to apply to or might get into and far more concerned that they have the habits, the mindset, the skill set, the wellness, to be successful wherever they go. What I'm saying is, our kids need us to be a little less obsessed with grades and scores and a whole lot more interested in childhood providing a foundation for their success built on things like love and chores.

Even with my Asian DNA, I still have a majority progressive style that I embrace at times and aspire to maintain. I re-read all of those parenting articles people have shared on Facebook with me; I’ve actually bookmarked the blog post, “I See You, Less-Than-Perfect Kid, and It’s Time We Ease the Pressure on Your Stressed-Out Soul” by Rachel Macy Stafford. The parenting style described in this post requires letting go of control and separating our own worth from our children’s success and life choices.

While many attributes of my parenting style might skew lower on the Tiger parenting spectrum, there are a number of examples that show that I indeed have the capacity for Wholehearted parenting. For example, both of the kids are okay at their chosen sports, but not extraordinarily outstanding. There are moments of challenge and disappointment when it comes to making teams, getting playtime, and performing for the team. I tell them that it’s about the effort, sportsmanship, team spirit, and that tomorrow’s another day. I offer empathy and support, really, I do.

We have also had plenty of indulgent moments that do not represent time wasted, but quality family time – mother/son whale watching to indulge his obsession with sea creatures, searching endlessly for open parking lots next to train tracks to perch and watch trains roll by when trains were the thing du jour, infinite treks to museums, cooking together, hikes, farms, parties, shows, and other bonding moments for pure fun.

Amy has thoughts on Western parenting philosophies:

Western parents try to respect their children’s individuality, encouraging them to pursue their true passions, supporting their choices, providing positive reinforcement and a nurturing environment. By contrast, the Chinese believe that the best way to protect their children is by preparing them for the future, letting them see what they’re capable of, and arming them with skills, work habits, and inner confidence that no one can take away.

70% of Western mothers said either that “stressing academic success is not good for children” or that “parents need to foster the idea that learning is fun.” What Chinese parents understand is that nothing is fun until you’re good at it. To get good at anything you have to work, and children on their own never want to work, which is why it is crucial to override their preferences. This often requires fortitude on the part of parents because the child will resist; things are always hardest at the beginning, which is where the Western parents tend to give up. But, if done properly, the Chinese strategy produces a virtuous circle. Tenacious practice, practice, practice Is crucial for excellence; rote repetition is underrated in America Once a child starts to excel at something — whether it’s math, piano, pitching, or ballet — he or she gets praise, admiration, and satisfaction. This builds confidence and makes the once no-fun activity fun.

I also understand the points that Amy makes about defending her stance about working toward excellence. But I do believe that kids need to know that they do not need to perform or achieve in order to attain their parent’s acceptance or love. I want them to know that life isn’t solely about getting the grade, but it’s more important to pursue passionate interests and put forth effort into all that they do. We can strike a balance of building their confidence and setting high expectations, while encouraging well roundedness. There isn’t a black and white answer, and my hapa kids are going to enjoy the best of both worlds. My third and fourth generation, Colorado-raised progressive stance, rooted in some Asian DNA, will continue to be the guide.

Happiness is a Choice

In her book, Amy is confidently at peace with how she has raised her girls:

Happiness is not a concept I tend to dwell on, Chinese parenting does not address happiness. It’s amazing how many Western parents I’ve met with who’ve said, “As a parent, you just can’t win. No matter what you do, your kids will grow up resenting you.” By contrast, I can’t tell you how many Asian kids I’ve met who, while acknowledging how oppressively strict and brutally demanding their parents were, happily describe themselves as devoted to their parents and unbelievably grateful to them, seemingly without a trace of bitterness or resentment. I’m sure that Western children are definitely no more happier than Chinese ones.

Chinese parenting is one of the most difficult things I can think of. You have to be hated sometimes by someone you love and who hopefully loves you, and there’s just no letting up, no point at which it suddenly becomes easy. Just the opposite, Chinese parenting, at least if you’re trying to do it in America where all the odds are against you — is a never-ending uphill battle requiring a 24/7 time commitment, resilience and guile. You have to be able to swallow pride and change tactics at any moment. And you have to be creative.

As I read Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, I felt relieved that my Asian DNA seemed to explain some of my internal conflicts, while also feeling gratified in knowing that the true Tiger parenting is off-the-charts extreme. I happily quoted some of Amy’s examples to share with my kids, demonstrating how lucky they really have it (“See? I could be way worse”). I also watched some of Amy’s interviews as the critical controversy surrounded her stories. Amy emphasized that it was a transformative journey for her, one in which she experienced a clash of cultures and was humbled by mistakes. While she says that this is definitely not a how-to book, she is steadfast in deeply believing that parenting should have high expectations combined with unconditional love. The book forced an introspection of my own self-awareness journey, and I certainly won’t argue with that premise.

Some of the best compliments I’ve had are at parent teacher conferences when they say, “You’re doing a fabulous job.” This affirms what we are trying to do — setting our kids up for success. It’s torturous, the constant self-righteous direction we thrust on our children and the resulting insecurity, shame, and guilt we have in trying to push them amidst Tiger parenting, Helicopter parenting, Lawnmower parenting, and Wholehearted parenting philosophies. We love our kids to death and agonize about the right things to do. We demand perfectionism, but we ourselves are far from it both now and in our own childhoods, when reflecting back. Perhaps parents deserve some grace as well.

What the last fifteen years have taught me is that I think our kids will turn out okay, and I’ll take only partial credit for that. I’ll continue to set high standards so that they aim for their best. I’ll support them when they make mistakes, but they will have to prove to me that they learned something from the experience. I really want them to take accountability for their own performance, whether failure or success. I’ll nurture both Eastern and Western parenting styles and acknowledge the gravitational pull I feel from both. And only I will know what strategy is appropriate to dial up or down and when. I’ll trust that instinct, as I will increasingly trust my young adult kids. And it will be more than fine, it will be gratifying and soul-fulfilling, just as this parenting journey is meant to be.