How Black Lives Matter Made Me Understand My Family and My Culture Better

“Wow, we left home for this?!”

It was November 1979, the cacophony of the LAX traffic in addition to the trash-filled sidewalk we’d rolled our luggage onto, created an atmosphere of unending grime. My family and I had just landed in Los Angeles from Manila. At that time, as Asians, we stuck out like aliens landing on Earth. We looked, spoke, and acted differently from the people around us. I wished I was back in the Philippines, but only for a moment…because from the moment we landed, we focused entirely on assimilation. We wanted and needed to fit in. Unfortunately, that meant shedding some, if not most, of our Filipino culture. Being an 8-year-old at the time, I never questioned my parents on this since supposedly anything American was, by default, “better” than what we previously had (at least that’s what I was made to believe).

In the ’80s, all Asians were grouped into one bucket. Chinese, Korean, Filipino, it didn’t matter. Most people didn’t know what a Filipino was or referred to the Philippines as the “Philippine Islands”. It’s not that I didn’t like being Filipino, but, at the same time, I wasn’t going to promote this fact either. I’ve lived in several places, but never in an Asian community. My parents never encouraged us to keep our culture because coming from an unusually religious family, (no, I mean UBER-religious), we were Catholic before we were Asian. So the church was more important than the culture. The church was the culture. Unlike most immigrants who tend to congregate, live among, and socialize with people from the same country, we searched out communities of the same religious faith. And, at that time, there weren’t very many Filipino-Catholic communities, so by default, we weren’t around our ethnic culture at all. This was the same story with school, where I mostly had blue-collar/middle-class white, Latino, and black classmates. As a kid, I hardly thought about what cultural heritage meant to me as an identity or as the foundational values for life, which set the stage for this past year of immense learning as an adult.

“Don’t rock the boat!”, “Keep your head down!”, “Just worry about yourself!”, is what we were taught growing up. Over time I realized these are common mantras almost all 1.5 generational Asians hear from their parents. We had left the Philippines in the midst of the President Marcos Martial Law regime (President Ferdinand Marcos placed the country under Martial Law in 1972. This lasted until his exile from the Philippines in 1986). With the loss of our civil rights (the irony which we would see later) and future opportunities beckoning, my parents felt that it was best to leave the country. We went from living a relatively comfortable lifestyle in our homeland to working paycheck to paycheck just to keep us afloat in the U.S. My parents were focused on making sure our family always had the basics of food and shelter. When you’re trying to sustain a large family, there is little time for attending after school activities, discussing the history of racism, or giving lessons on social justice.

I didn’t fully understand my parents’ motivations until much later. As an adult with a family of my own, there was even a period of time when I felt resentment towards my parents because I thought I didn’t know enough about our culture to pass down to my daughter. However, as I write this, I get it. I am fortunate to not have to worry about half the things my parents had to deal with when moving our family to this country. In a roundabout way, even if they didn’t teach me these values directly, their hard work gave me the luxury of time and space to learn to be more progressive (even though I’m sure that’s not what they were intending). Their “keep your head-down” ethos in work and life provided me with sufficient security to think past taking care of myself and look more closely at the state of my circle, my community, my country, and the role I play in them.

Fast forward to 2020 and COVID-19. Chinese people as well as all Asians are being blamed for the spread of the virus. Every Asian is being put in the same bucket again, just like in the ’80s. Apparently, the more things change the more things do stay the same. Between COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement, this year of protest and civic action has opened my eyes wider to systemic racism, pushing me to learn more and do something about it.

During the L.A. riots in 1992, as a young man five years older than my daughter is now, I watched things unfold on my parents’ TV: the non-guilty verdict, the protests, the rioting. The social unrest going on around us didn’t matter to my parents as long as it didn’t affect them directly. Thinking back, I’m ashamed that I didn’t do anything then to counter their beliefs or speak up for what I knew was right. Asians are stereotypically thought of as the “quiet ones”. And for years I believed that just like my family did. I learned how very wrong I was, thankfully. Asians have historically been getting into “good trouble”, as John Lewis would put it. From Grace Lee Boggs to Yuri Kochiyama to Larry Itliong and numerous others, Asians have been active civic participants and in the middle of movements for social justice. As part of the team that developed the Make Noise Today initiative, I feel like I am helping change the mainstream narrative about Asian Americans and placing myself on the frontlines for encouraging a nationwide conversation about race and racism. In my heart, I am trying to make up for the times that I stayed quiet on supporting all people of color and marginalized communities.

I’m thankful to see that my daughter isn’t going to need to make up for lost time when she’s grown up. As a parent of a mixed-race daughter, it might seem like it’d be tougher to pass down any of my cultural heritage. However, I have been extremely fortunate. First, my wife, who is not Filipino, has always embraced other cultures and believes that diversity only enriches, never restricts. She has encouraged and looked for ways for me and my daughter to connect with our ethnicity, be it through food, language, traditions, or more. Secondly, because of the internet, my daughter has seen many more Filipinos and other Asians in entertainment, media, and culture than I ever did at her age. Distinct Asian cultures and multiculturalism are celebrated now, no longer lumped together and looked down on to the same degree as in the past (at the same time, this year we’ve seen how even when things seem to have changed, they might not have changed as much as we hoped).

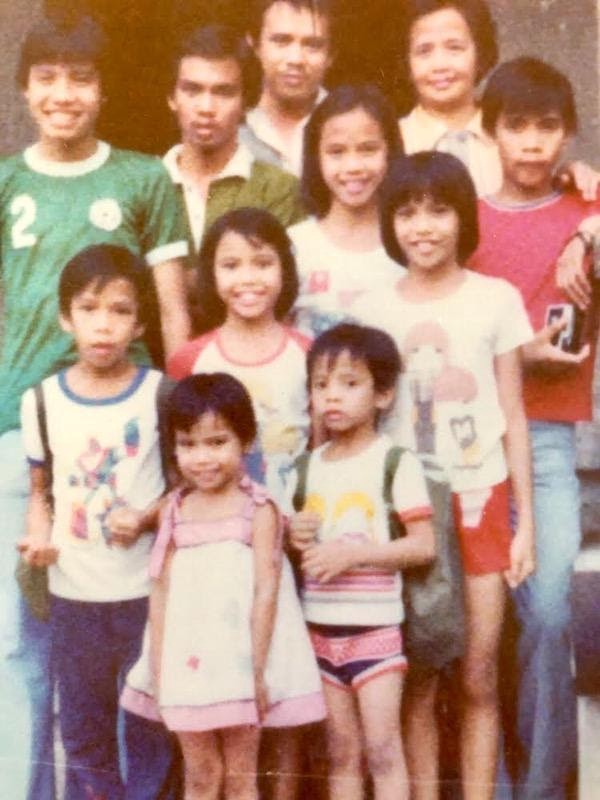

And lastly, I compare the way my parents raised me to how I’m trying to raise my daughter. They were making sure that the basics were met…and when you’re the seventh child out of nine, parenting doesn’t tend to reach down that far. So there were a lot of mistakes I had to make and lessons I had to learn on my own. Based on this, the family dynamic I have with my wife and daughter today is much different compared to the one my siblings and I grew up with. Social awareness and activism have been a catalyst for my retro-acculturation and searching out a deeper understanding of my cultural heritage. My personal growth will help me provide my daughter with a stronger connection to her Filipino heritage. Above any traditions or cultural values, I hope that she understands how to be a proud person of color who embraces the responsibility of fighting inequalities, not just for her but for all marginalized communities — never believing that it’s her role to “keep her head down.”