Do you see me?

Feeling invisible

I’ve never been one to feel invisible. There were times in my life where I wanted to blend in, not be seen, and even be invisible to those who pointed out my differences but that was when I didn’t speak English. I recall watching Charlie Brown as a kid and realizing that the way teachers spoke to the kids was exactly how I heard English speakers. Folks were cruel to mock my accent or language fluency. It was always shocking to me when adults treated me, a then 7 year old, with such disdain because I didn’t speak English, didn’t dress like other “Americans’, and didn’t understand them. For a full year, I decided to stay quiet. I wanted to be invisible and to blend in and not stand out. I did not want to make waves in fear that it would alert others to the fact an outsider was in their midst. After a year of observing Americans through a young immigrant child’s lens, I quickly learned that in order to succeed, one had to not blend in and to speak up whenever possible.

As I write this, I realize that it is much easier said than done. The process of figuring it out was tumultuous at best and quite straining. I remember thinking that it would all be easier if I wasn’t alive. I thought this when I was just 10 years old. As a 1.5 generation child who spoke English better than her parents and had to also care for a younger sibling, I felt deprived of a childhood. I learned about paying bills, translating for my mom, and going to parent teacher conferences for my younger sibling. I had to take on adult responsibilities early, and it was just too much. I didn’t want to handle finances, make appointments with teachers and doctors, and translate documents for my mom. I wanted to be a kid like my peers, but that was not to be for me.

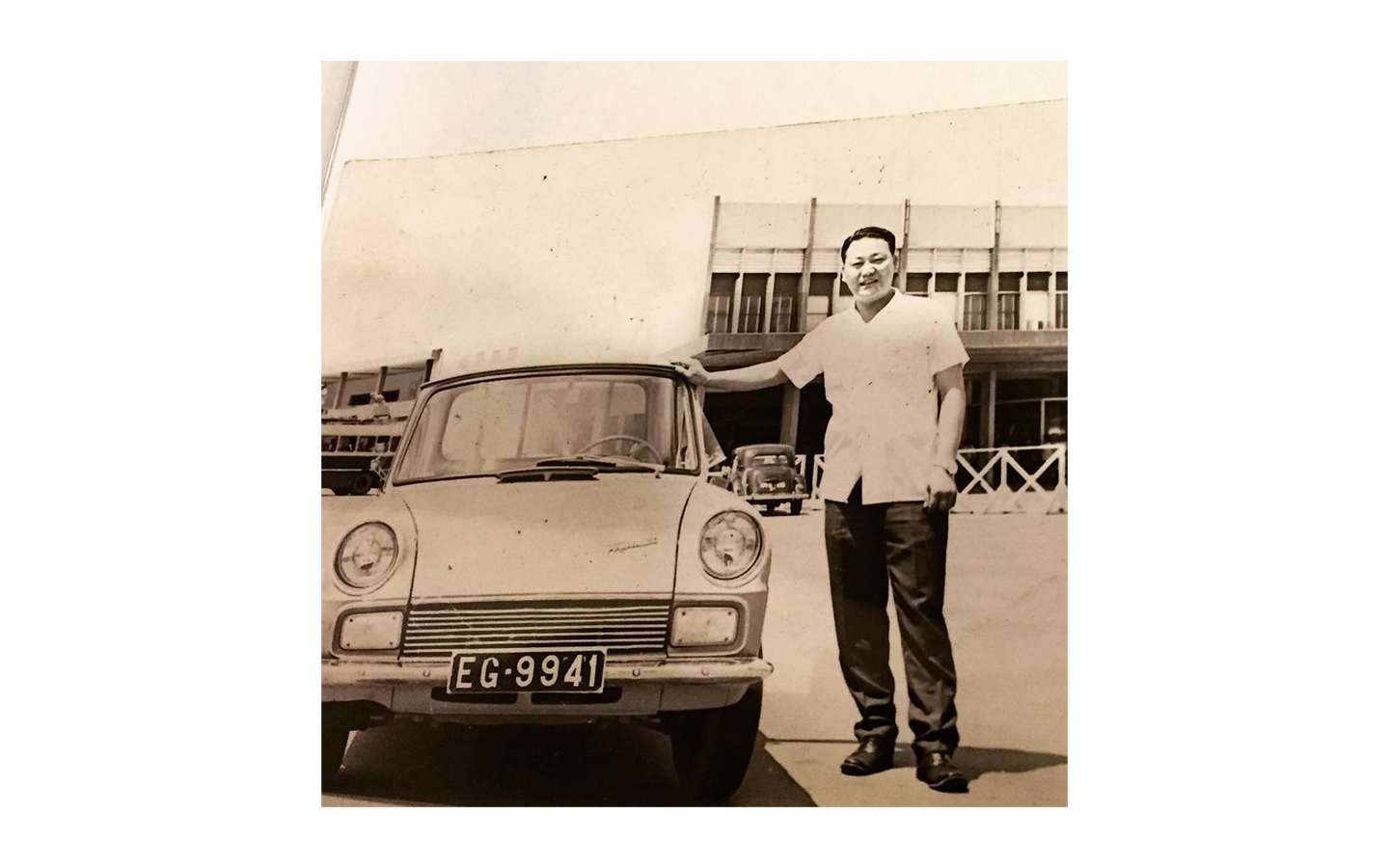

As an immigrant child, my life was significantly different than most. I worked at my dad’s liquor store as early as I can remember. I started helping him at age 8, but slowly working the cash register and helping with stocking the shelves at age 10. I observed the streets of San Francisco during the 80s in the Mission and Tenderloin areas, and I interacted with drug dealers, police officers, homeless, working people, and other “regulars” who requested a hot dog, Poorboy, pigs’ feet, Marlborough lights, or a Thunderbird. I handed over the bottles of Night Train to our customers as our police friends watched.

These early interactions and exchanges helped me appreciate the human condition. The resilience of the people who came through our stores. While folks were making “bad decisions” in life, I learned quickly that they were not bad people. I learned to ask questions, learned to have sympathy and, later, empathy for those who I saw every day. These people with hardships saw me as a kid. These people who had little treated me with kindness. I rarely heard “go back to where you came from” from the customers. I did, however, hear it from others.

Go back to where you came from

I never quite understood that statement: “Go back to where you came from.” As a child immigrant, I knew that we immigrated from Korea, but we also stopped in Guam and in Hawaii before settling in San Francisco. Why did they see me as a nuisance? Why did they want me to go back? Why did they despise me so? I learned at a young age what racism is. I faced it on the daily, but I also saw my parents and their friends relay racist sentiments about African Americans and “dark” people. The othering of our communities is an old tactic that victims of racism use to oppress other groups as well. Somehow if you are superior over another, you are less subservient?

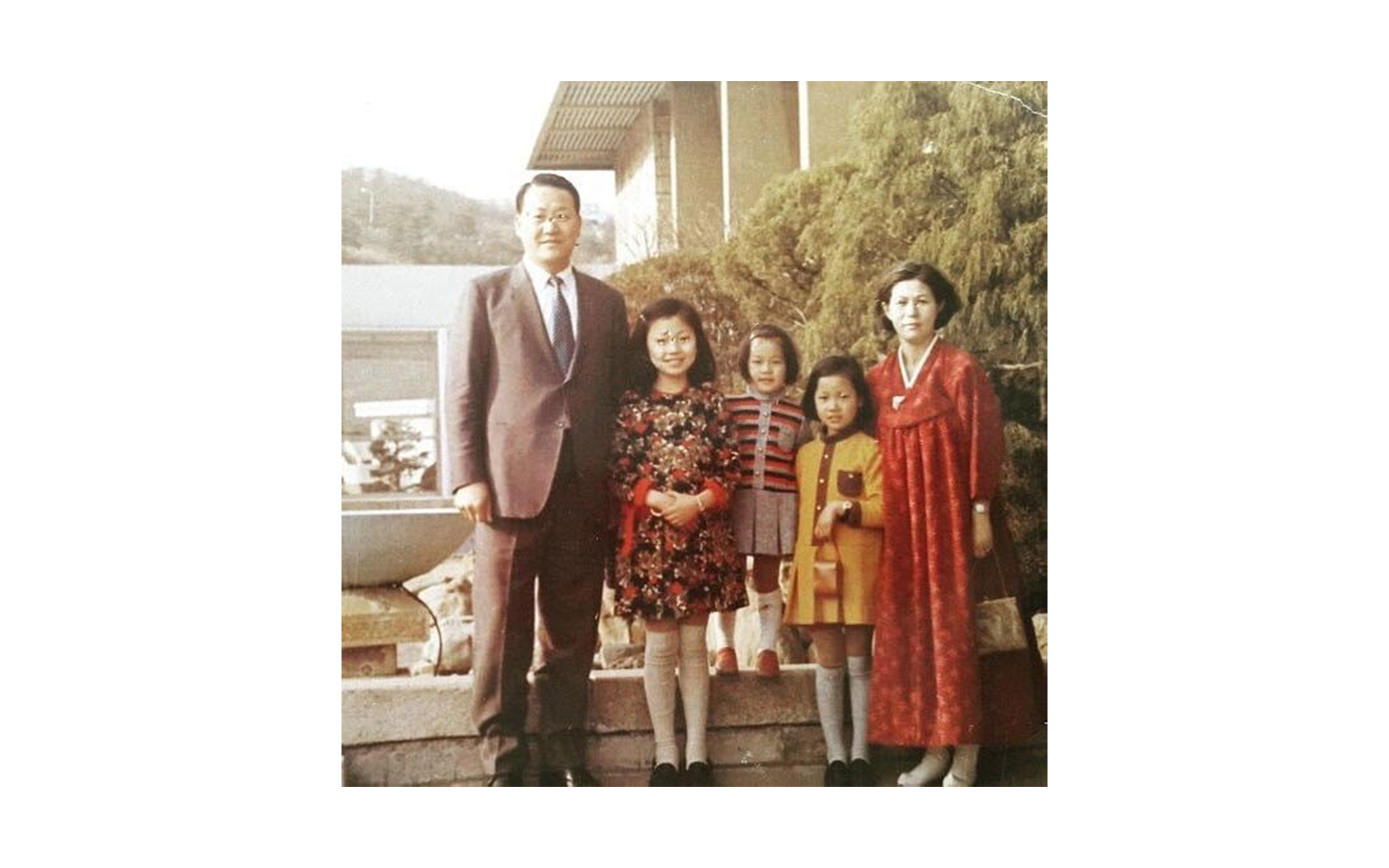

I became a vocal teen and an assertive college student who wanted to just finish school. However, I never really wore my Asian American identity on my sleeve. In fact, I never really felt Asian American. When my mom called me a banana (yellow on the outside and white on the inside) I was offended, but I knew why she thought this. I was more Americanized than my parents and I acted “white", but I maintained Korean pride. I knew I was Korean, although others told me that I was Chinese despite me correcting them. I was told that it was all the same. I spoke Korean, ate Korean food, and had memories of Korea, but I also knew that I was not like my parents.

Later on, I wrote the first book on children immigrants like me titled “The 1.5 Generation.” Yet throughout college, I didn’t identify as Asian American. I was assertive and proud, but

I was not woke to what it meant to be Asian American. At this time in my career, I did not yet have ethnic studies under my belt. I was a natural sociologist interested in race, but never once really examined my own positionality.

Don’t see me

The way racism works in this post-Jim Crow and civil rights period is to have us internalize it. The implicit biases that are assigned to communities of color are internalized and actualized. Furthermore, we internalize the various racist stereotypes about our own groups, in bizarre ways, as we dismiss our own identities. As an Asian American woman, the paradox of my identity was that I wanted to both be seen and not seen. I didn’t want to be seen for my race, ethnicity, or immigrant status. I didn’t want to be seen for my ESL status, the “bizarre” foods that I grew up with, and I didn’t want to be seen as the other. Yet, I quickly realized that no matter what I did, do, or say, I was seen as the other or the exception. When folks heard me speak, I didn’t sound Asian. And when I stood up for myself, I was atypical because I spoke up and resisted problematic narratives. I wanted the micro-affirmation, but never got it.

Wake me up when it’s time

I have to admit that I was asleep when it came to race and sexuality for most of my young life. The feeling of alienation and marginalization was always framed around my immigrant Asian identity. While I didn’t want to address it, I really wanted someone to fix it, but did not want to be bothered with it. In 1992 I woke up. On April 29, 1992, the first multiracial riot included my community. I watched, surprised to see LA on fire, and the narrative was that it was a Korean Black conflict. I watched Korean merchants on their roof tops shooting at incoming rioters and looters of all racial communities. It was, in fact, the first multiracial riot, yet the framing of the conflict flamed the tension that already existed between Blacks and Koreans. I understood this.

Growing up, we were the Asians or “Orientals” in the “hood” or the “bad neighborhood” where no one else wanted to be. We were the ones working at the liquor stores in the poor neighborhoods that people avoided. There were language barriers, cultural challenges, and, definitely, initial fears of each other. I heard about what happened in New York and Los Angeles, and it shocked me. Not because I was asleep, but because these communities, at least the ones I grew up in, were not strange to me. They were not my enemy. They were our regulars and some friends.

I immediately called my dad and asked if he was ok. I knew that the LA riots were in South Central, but I also saw on the news that the riots were spreading and I began to worry. Surprisingly, he told me that all was ok. He said a group of the regulars stood outside his store to protect it. I was heartened to hear this. I knew that our family built relationships with our regulars, but to hear that they had our backs when it counted meant so much. I turned to my Black roommate as we watched the news broadcasting that this had happened because of the Black and Korean conflict. We looked at each other and laughed at this odd moment and said, “Hey, I didn’t know we didn’t like each other.”

To be clear, the LA riots were not about the Korean Black conflict. It was about racism, police violence, and the racial profiling of Black lives. Before Black Lives Matter emerged, the beating of Rodney King was the first of many videotapes of violence against Black bodies and, in particular, Black men. The common experiences of Black men were captured on tape, yet the officers who were videotaped using excessive force were acquitted. That became the watershed moment for communities of color to say, “Enough.” The riots were not an attack on communities, but a revolt against police brutality and institutional racism. It was also the moment when I woke up.

About Mary

Mary Yu Danico received her PhD in Sociology from the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She is the director of the Weglyn Endowed Chair for Multicultural Studies , Director of Asian American Transnational Research Initiative, and Professor in Sociology at Cal Poly Pomona. She is the past president of the Association for Asian American Studies and Fulbright senior scholar. She is the author of 1.5 Generation: Becoming Korean American in Hawaii (UH Press), Asian American Society (Greenwood Press), Transforming the Ivory Tower: Challenging Racism, Sexism, and Homophobia in Higher Education (UH Press), and editor of Asian American Society (SAGE PRESS), one encyclopedia, and numerous articles.