Asian Americans in Hollywood: The Effects of 20th Century Stereotypes

Movies play such a huge role in our society today and influence the way that we look at the world. Hollywood movies are a representation of our society, a concrete reflection of the time we live in and what we value. Movies are a way to tell one story to millions of people around the world. With that power, movies can create, reflect, and perpetuate stereotypes, and can mold the way that society sees a certain people group. For Asian Americans in the early 1900s to the late 1960s, the stories being told about Asian people by Hollywood were overall pretty negative. In a society that rejected change and actively worked against anything different from the status quo, the portrayal of Asian people in Hollywood films was a direct reflection of what White Americans thought of Asian people at the time.

As a young, movie-loving Asian American in the 21st century, to me these movies feel like ancient history, stories from long ago that have no more cultural relevance in today’s society. While that could be true in some respects, racism and discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans continue to persist in America today, and Hollywood remains a good representation of what that looks like. While anti-Asian racism may not be as blatant as it was before, it still persists, and knowing its roots helps us understand where it comes from, why it took hold, and how we can combat it.

Hollywood as a Reflection of Society

Chinese people were the first major Asian immigrant group to establish themselves in the United States back in the 1850s during the California Gold Rush, and many families here can trace their origins back to that time. While initially welcomed with open arms, anti-Chinese sentiment quickly rose as large groups arrived seeking a better life in America. They were willing to work for lower wages at jobs that few White Americans wanted, such as field workers, launderers, and housekeepers. With few “respectable” jobs available for Chinese immigrants, they were at the bottom of the social ladder in a White dominated society; this was the cost of being an Asian in America. Yet despite the low social standing of Chinese people in society, White Americans began to feel threatened by their presence and their “deviation” from what was “normal.” As sentiment shifted and open hostility towards Asian people in America grew more and more present, the U.S. government passed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting any more Chinese immigrants from entering America. This was the first ever act passed prohibiting an entire ethnic group from immigrating to the U.S.

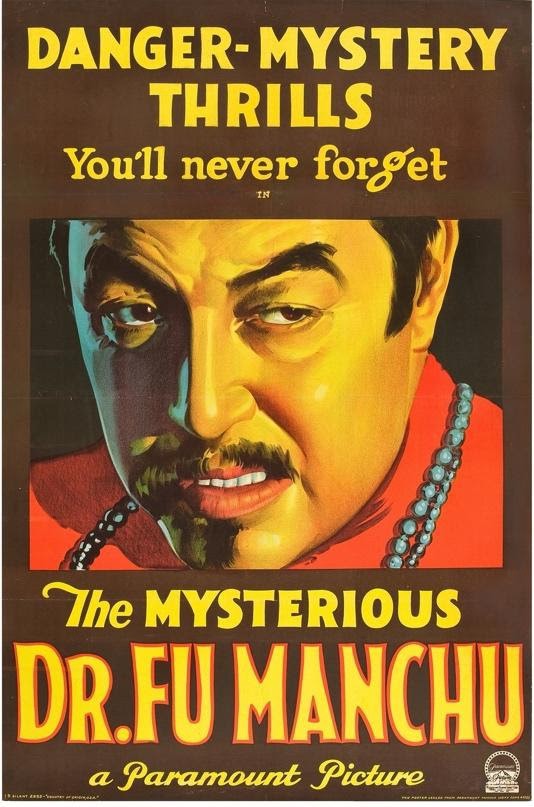

Hollywood, rather than combatting the prevalent anti-Asian sentiment, reflected and perpetuated the overall distrust of Asian people through films such as The Cheat (1915), The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929), and The Thief of Baghdad (1924); pushing the narrative that is now known as “yellow peril”. Yellow peril was the idea that Asian people from the East threatened the Western way of life and sought ways to destroy it. Through the eyes of Hollywood, Asian people, namely Chinese, played very few and very subordinate roles in movies and in real life. In addition, since Hollywood, and people in general, were distrustful of Asian people, when showing an Asian character in films, Hollywood used yellowface. Yellowface refers to a non-Asian actor portraying an Asian character with the use of makeup, prosthetics, and costumes to give them “Asian features” or an “Asian look.” This look was based on heavily exaggerated stereotypes, such as small/slanted eyes, large teeth, and a flat nose while wearing “Asian looking” costumes. While this is clearly racist, yellowface in Hollywood continued to be common because a White actor might express a casting preference or interracial contact had to be minimized due to laws prohibiting it.

In addition to leaning on heavy stereotypes when portraying the look of an Asian person, Hollywood also saw the “essence” of Asian people in a limited number of typecasts. The most frequently used typecasts for Asian characters in the early 20th century were the Lotus Blossom, the Dragon Lady, and the Fu Manchu.

The Lotus Blossom

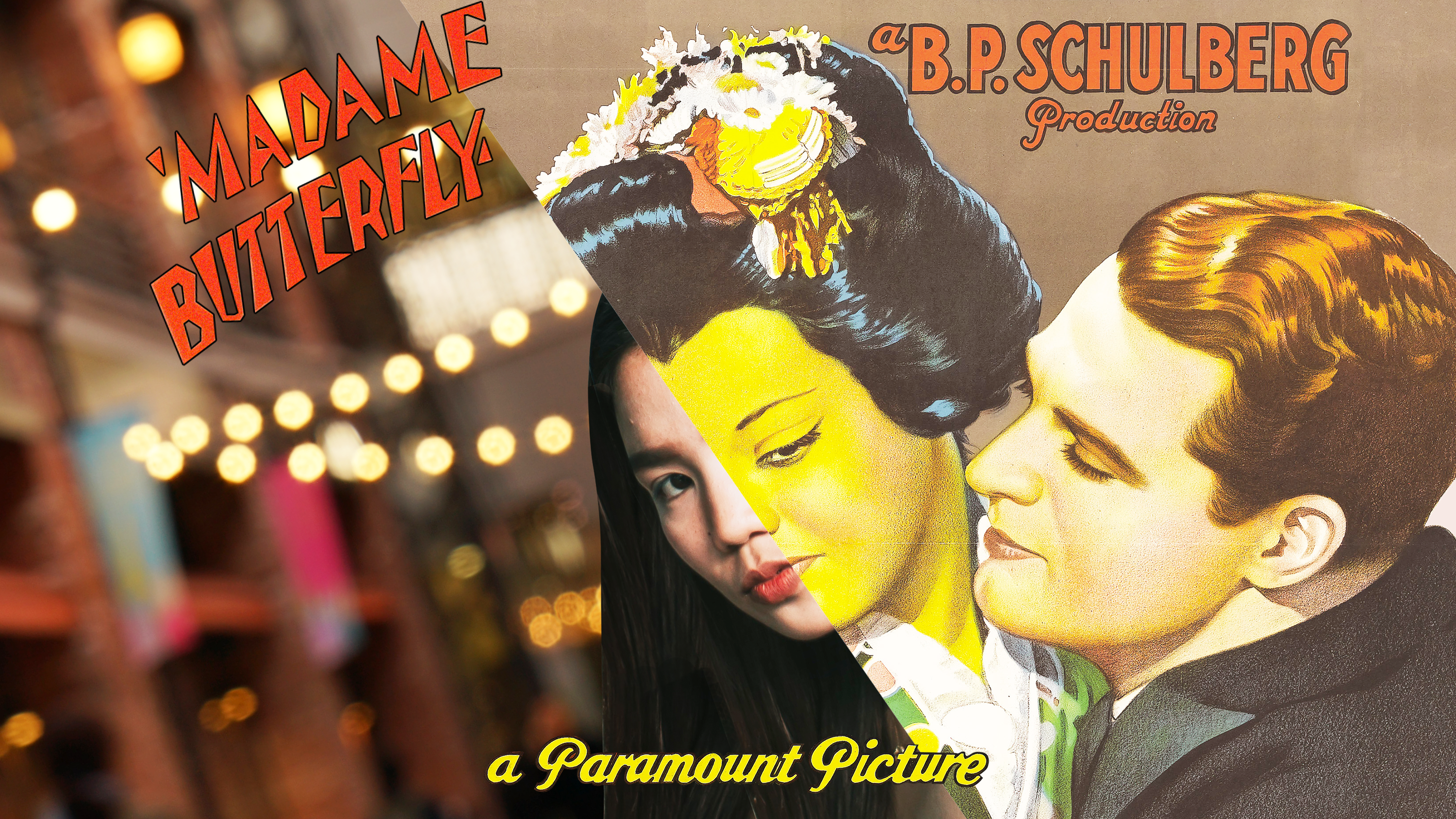

The Lotus Blossom, also sometimes referred to as the “China Doll,” is a stereotype of Asian women as being passive, docile, and subservient — characteristics that were for the purpose of pleasing a White man. At the same time, the Lotus Blossom is also cast as being sensual, mysterious, and exotic; something new and unfamiliar to the White male. Since the role of the Lotus Blossom is to be subservient to whatever the White man needs, she is often hypersexualized, as she exists just to please the sexual desires of a White man. Some examples of the Lotus Blossom in early 1900s films are Lotus Flower in The Toll of the Sea (1922), Cho Cho-San “Butterfly” in Madame Butterfly (1915 and 1932), Katsumi in Sayonara (1957), and Suzie Wong in The World of Suzie Wong (1960).

Although more common in the 1900s Hollywood era, the idea of the Lotus Blossom still lives on today, both in movies and in our society. Movies from the 1970s to early 2000s continued featuring the Lotus Blossom in many popular Hollywood movies. These classic movies influenced many late Boomers, Generation X, and early Millennials in their most impressionable years on the definition of an Asian American woman and how she’s “supposed to act.” The people being influenced by these stereotypical roles grew up to become our parents, grandparents, teachers, politicians, etc., who influence who we, as young Asian Americans can become. The existence of the Lotus Blossom stereotype contributes to the continued hyper-sexualization and fetishization of Asian and Asian American women. I have noticed that, especially in the modern dating scene, people still perceive Asian American women as “exotic,” passive, and obedient in relationships; character traits not as commonly expected from women of other races. This, in part, contributes to the phenomenon known as “Yellow Fever,” a preference for Asian people in the dating world based on harmful and untrue stereotypes.

The Dragon Lady

The stereotype of the Dragon Lady falls on the complete other end of the character spectrum in some ways, yet still shares certain traits with the Lotus Blossom. Instead of being docile and subservient, the Dragon Lady is a dominatrix: powerful, manipulative, and seductive. While in juxtaposition to the weak and helpless Lotus Blossom, the Dragon Lady is also hyper-sexualized, again to fulfil White sexual fantasies. The Dragon Lady is strong and in charge, exuding feminine charm and seductive energy; almost toying with male characters using her power. Representing two opposite ends of the spectrum, there is little representation of Asian females anywhere in between the Lotus Blossom and the Dragon Lady, especially in the early 1900s Hollywood movies. Some examples of the Dragon Lady in films of that era are the Mongol Slave in The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Ling Moi in Daughter of the Dragon (1931), and Hui Fei in Shanghai Express (1932). These two stereotypes were essentially the only types of representation that Asian females received in Hollywood at the time, with very few, if any, roles outside of these two typecasts. As typecasts, both roles are extremely one-dimensional, with little deviation from the racist stereotype and no character development.

Similar to the Lotus Blossom, the Dragon Lady stereotype and its effects continue to live on in mainstream media and our modern society. With little mainstream representation of anything in between the Lotus Blossom and the Dragon Lady, people assume that Asian women fall under one or both of those categories. Since both of these stereotypes fetishize and hyper-sexualize Asian women, it is possible that these stereotypes contribute towards men of all races finding Asian women to be overall most desirable in the dating world compared to women of other races. In 2013, researchers took data from the Facebook app Are You Interested, reviewed 2.4 million heterosexual interactions, and found that men of all races (except Asian men) prefer Asian women. Since it is likely that the preference comes in part from inaccurate stereotypes, a result is that Asian women become targets for sexual harassment and are forced to navigate around fantasized perceptions of who they are.

The Fu Manchu

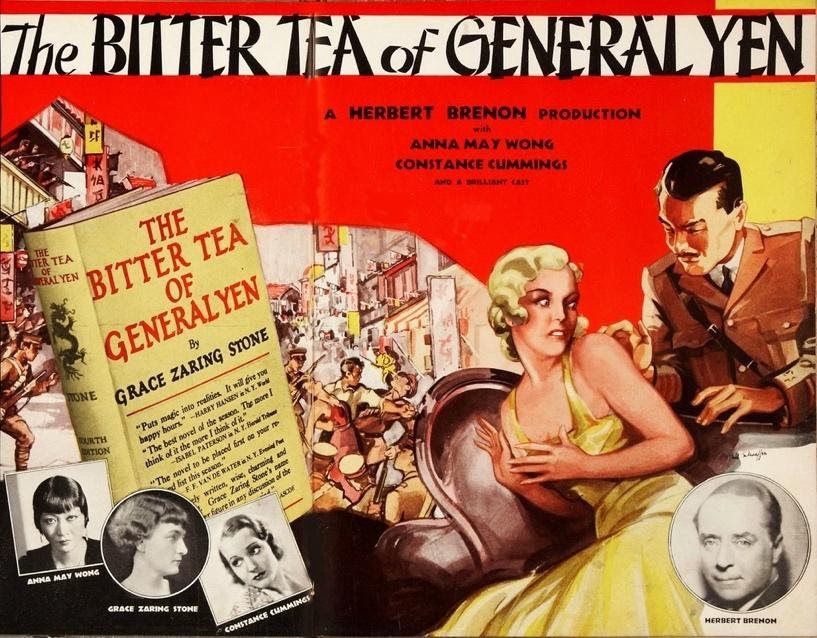

While the Lotus Blossom and the Dragon Lady are stereotypes for the Asian female, the stereotype of the Fu Manchu was one of the few roles for Asian males. The Fu Manchu stereotype comes from a 1913 series of novels by Sax Rohmer (1883–1959). In “The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu,” which revolves around the evil doings of the dastardly villain and evil scientist Dr. Fu Manchu, Dr. Fu Manchu repeatedly tries to gain world dominance for China and attempts it by any means necessary. The series was eventually adapted into 15 short films and 3 Hollywood movies. Dr. Fu Manchu was described by Rohmer in the first novel as “the Yellow Peril incarnate in one man.” This type of character, an Asian man set on destroying the American way of life, became the embodiment for the Asian male in the eyes of White Americans. The Fu Manchu character also perpetuated the “otherness” of Asian people, implying that they will always be different and “foreign” and can never be considered American. Some examples of the Fu Manchu in early 1900’s films are Haka Arakau in The Cheat (1915), General Yen in The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933), and Colonel Saito in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957).

Personally, I think the legacy of the Fu Manchu, out of the three stereotypes, has the strongest effect on our society today. While the Lotus Blossom and the Dragon Lady are, for the most part, stereotypes primarily existent in media, the core characteristics of the Fu Manchu continue to hold strongly in people’s perception of Asian Americans today, 100 years later. The Fu Manchu stereotype revolves around the idea that Asian people are loyal to their “home” country and will do anything to advance the interests of the “motherland”, even if it means destroying the Western way of life. This stereotype was not only destructive when it originated in the early 20th century, but it continues to contaminate the minds of people now, causing them to believe that all Asians are loyal to their “home” country. This is most visible in the common question that all Asian Americans get asked at some point in their life, “Where are you REALLY from?” Implying that we are not American, but rather hold roots in a foreign country. This shows that regardless of how “American” you are, because of the color of your skin, you can never be a “true American.” As a 5th generation Japanese American, whose family first came in 1907, I am as American as they come, and yet still face racial prejudices that say I don’t belong and should “go back to [my] home country.” The Fu Manchu stereotype enhanced the idea of “otherness,” and has long prevented Asian Americans from being seen as American. The Fu Manchu gave a face and a set of characteristics to Asian people that has outlived many other stereotypes of its time.

Continuing to Reconcile with Hollywood Representation

The Lotus Blossom, Dragon Lady, and Fu Manchu characters reflected and enforced people’s negative perceptions of Asians, putting Asians into tiny boxes as to what and who they could be.

Although the stereotypes of Asian people in 1900’s Hollywood feels so long ago, these stereotypes continue to persist in today’s society and are reflected in today’s movies. While not as blatant and outright racist as they used to be, Hollywood has evolved and found more subtle ways to work these stereotypes into the Asian characters they portray. Understanding these stereotypes and where they originated from is important in being able to dismantle them and move into a new era of Asian representation in Hollywood films.