Asian American Millennials are Dispelling Model Minority Myths

The model minority myth presents oversimplified beliefs about Asian Americans, characterizing the group as achieving universal socioeconomic success compared to the general population and relative to other racial minority groups. However, Asian American millennials may be confounding this stereotype, both in their attributes and perception of themselves.

Asian American success is often measured by income, education, business ownership, and health. In doing so, people consider this group to be monolithic, ignoring the nuanced experiences of the various ethnic segments, which also differ across generations and immigration waves. Grouping many ethnic communities under the Asian American umbrella masks the true diversity within this group and overlooks the disparities in challenges that Asian Americans face.

“The model minority stereotype is still alive and well,” — Dr. Bob Suzuki

Since the mid-1960’s, media, politics, and education have continued to highlight and promote the model minority myth. Although it has become slightly less evident, the myth is subconsciously embedded in the public mind and continues to influence the way Asian Americans are perceived. Asian Americans are labeled as geniuses, Ivy Leaguers, hardworking, wealthy, and considered likely to become doctors, accountants, or engineers, striving to live an “American Dream”. One must avoid an Asian F at all costs.

The image of Asian Americans as successful, upwardly mobile overachievers creates a false set of expectations for millennials and future generations. Too often are the real diverse experiences of Asian Americans ignored, leaving many feeling like outliers alienated from the group.

The research findings of a survey conducted by the Asian American Transnational Research Initiative (AATRI) at Cal Poly Pomona of the Southern California population demonstrate that Asian American millennials exhibit nuanced characteristics that conflict with model minority stereotypes.

Financial Uncertainty

A major stereotype of Asian Americans is that this group is wealthy and high-income earning. Many reports have continued to draw attention to Asians ranking as the highest earning racial and ethnic group in the U.S. overall. Broadly, Asian Americans are perceived to be well-off and likely to achieve high economic success.

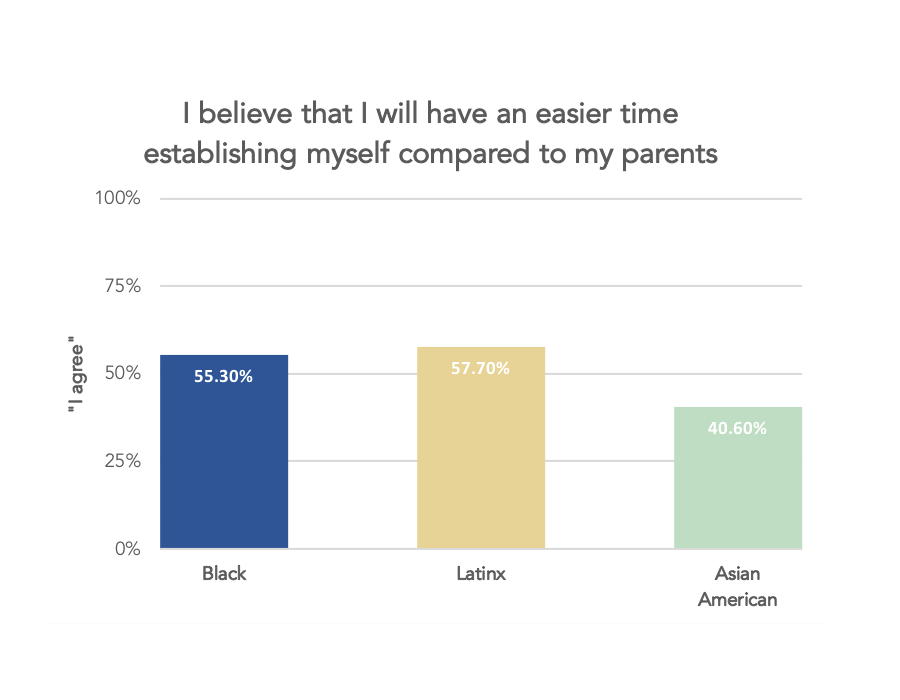

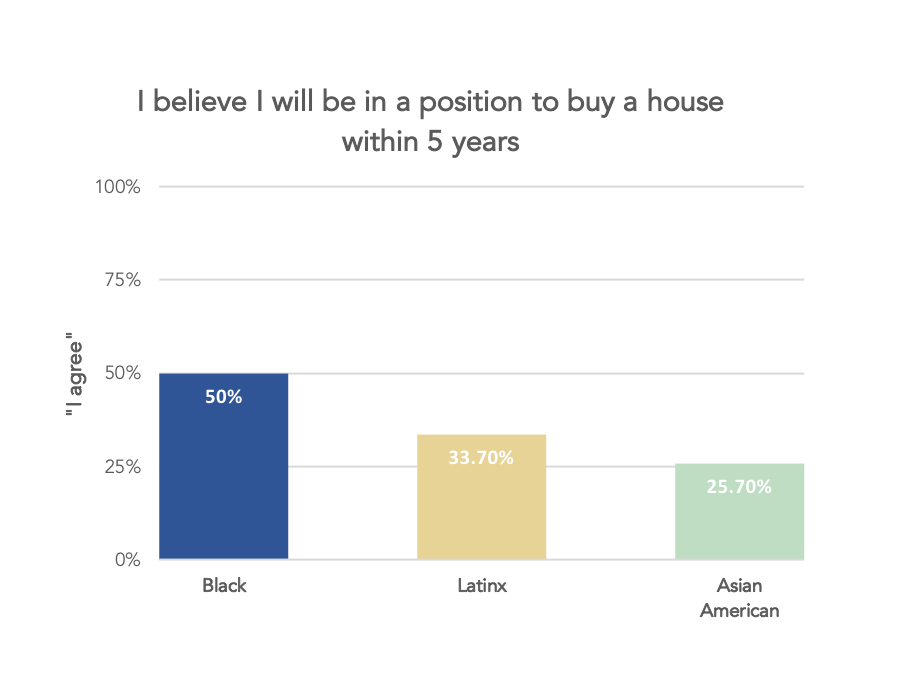

Despite such assumptions about their financial status, the Generations Study reveals that Asian American millennials currently experience feelings of uncertainty about their financial situation and future outlook. Although Asian American respondents do believe that making money is an important aspect of a job, they do not believe that they’ll have an easier time establishing themselves compared to their parents — the lowest level of agreement compared to their Black and Latinx counterparts. Moreover, only one-fourth of Asian American respondents feel that they will be in a financial position to buy a house within the next five years (the lowest again compared to Black and Latinx students).

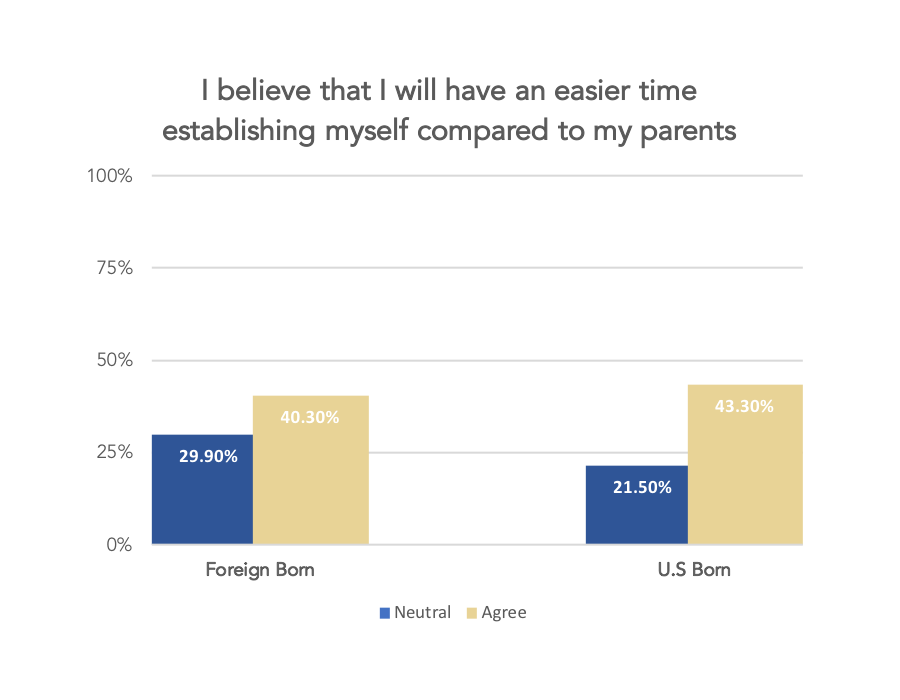

Significantly, the data shows that across generations, when asked whether they believe they will have an easier time establishing themselves compared to their parents, 40% foreign-born and 43% U.S.-born Asian American students agreed. However, it is important to note that 30% of foreign-born Asian Americans responded as neutral and 21.5% U.S.-born Asian Americans responded as neutral as well.

When compared to their racial counterparts, Asian American millennials do not seem so optimistic about their financial situation and, in fact, show signs of being financially unstable, which is very unlike the model minority stereotype of Asians having high economic well-being. These feelings of insecurity may be due to the financial crisis in 2008 that left many unemployed during their formative years and skeptical about the markets. When considering generation status, immigrants and 1.5 individuals had to acculturate to the U.S and become pseudo-adults in order to make ends meet for themselves and their families. They were more likely to take on adult responsibilities, eventually leading them to become more independent and self-sufficient. Whereas U.S. born Asian Americans, who are mostly children of immigrants, are supported financially by their immigrant parents. At the same time, however, they had to witness first-hand the struggles their parents faced to support them.

Ultimately, the feelings of financial uncertainty extend beyond generation status, and may largely be due to income inequality that already exists within the Asian population. According to the National Asset Scorecard for Communities of Color (NASCC) survey, there were significant disparities within Asian Americans living in the Los Angeles Metropolitan area. Japanese, Asian Indians, and Chinese households had higher median wealth than Whites; however, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Korean households had a much lower median net worth than Whites. In a recent Pew Study, income inequality increased the most amongst Asians from 1970 to 2016. Data shows that Asians in the top 10% of the income distribution earned 10.7% more than Asians in the bottom 10%.

Asians have become the most economically divided group in the U.S, yet aggregated data fails to acknowledge the distinct financial differences between ethnic groups. As a result, the most vulnerable groups within the Asian American community have their needs obscured and resources withheld, damaging their opportunities to build financial security and leave lives of poverty.

Career Insecurity

Oftentimes, people assume that every Asian is good at math, excels at school, and is highly educated. They are perceived to be naturally smart and likely to pursue careers in STEM, medicine, or accounting.

The reality is that Asian American millennials report relatively low job satisfaction rates (32.7%) in comparison to their Black (50%) and Latinx (41.4%) counterparts. These low percentages may be because their current jobs aren’t positions that they see themselves pursuing as careers. This would be in line with data that indicates Asian American millennials are not so optimistic about their career paths. More significantly, the Generations Study reveals that Asian American millennials report the lowest percentages of believing that they will work in their desired career fields within the next five years. Not only that, but graduate school isn’t an option for many as well, as only 54% reported they have plans to continue their education post-graduation.

Existing literature expounds on how Asian Americans experience subtle and overt discriminatory actions, and barriers like the ‘bamboo ceiling’, within the workplace. Moreover, they are still underrepresented in executive and management positions. In an article by Harvard Business Review, researchers have found that when looking at Whites with similar jobs, job experience, and levels of education in comparison to Asian American workers, Asian Americans were paid much less and were less likely to be promoted to managerial positions. The irony here is that Asian Americans are perceived to be qualified since they are supposedly “well-educated” and “smart,” yet there are no opportunities for this group in upper management.

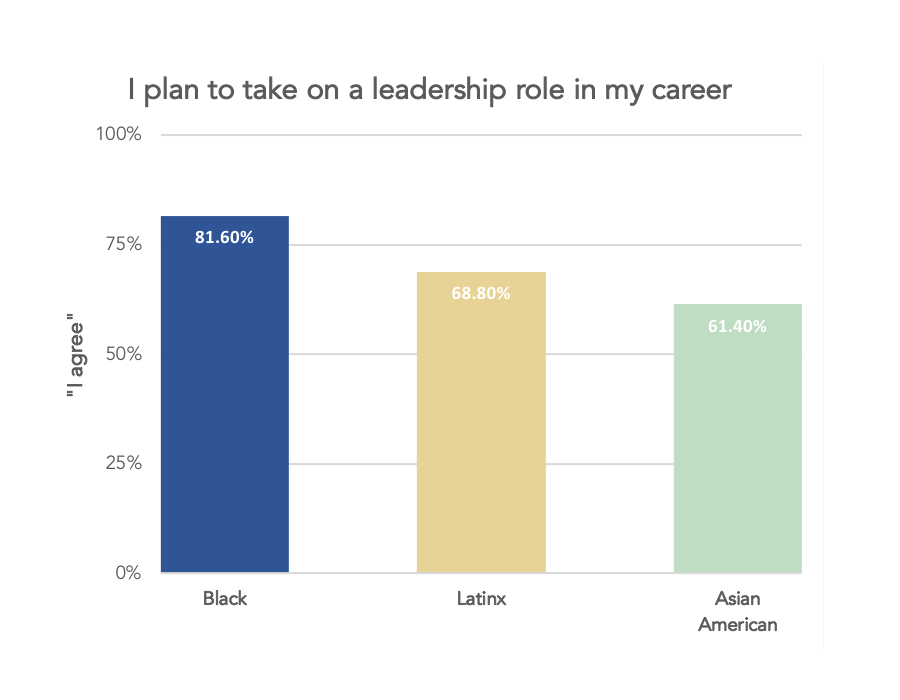

The same Cal Poly Pomona survey reports that Asian American respondents are least likely to say that they plan to have a leadership role in their careers (61.4%). This is not surprising considering that the model minority myth has created pervasive assumptions about Asian American workers that excludes them from an array of business positions. Many businesses do not consider Asian Americans to be an underrepresented minority and this blind spot may leave this group out of special considerations. This confluence of reasons leads to Asian American millennials seeing themselves in such a way that they do not even try to climb the corporate ladder.

Health Concerns

“Asian don’t raisin’” is the phrase used to describe how youthful older Asian Americans look. The model minority myth has normalized the belief that Asian Americans are typically healthier than the average White American. The myth has more commonly addressed areas such as income, employment, and educational attainment, but health has become another topic added to the list.

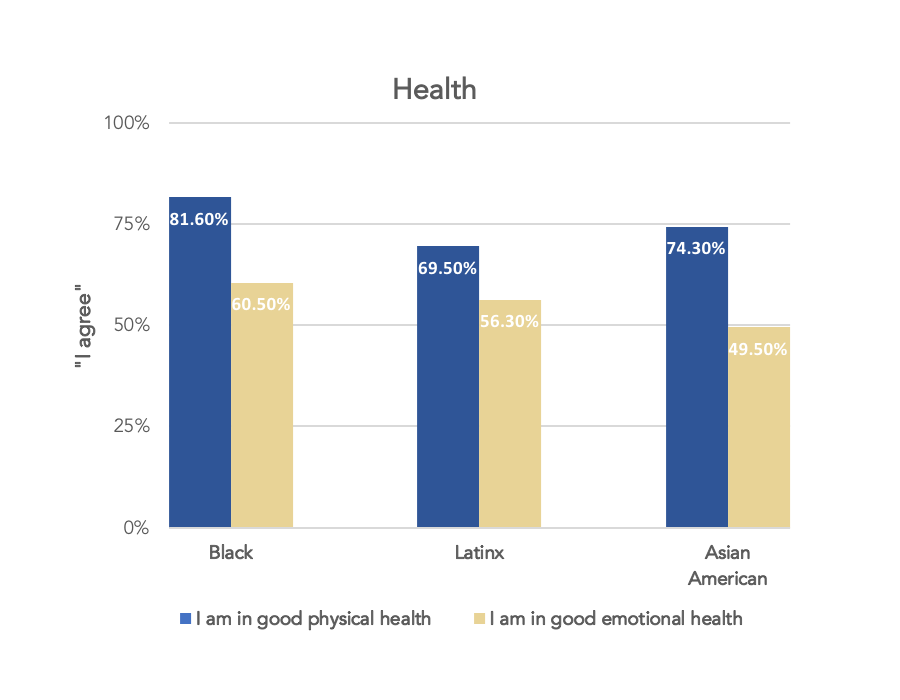

Although Asian Americans millennials do report that they are in good physical health (74.3%), they report the lowest percentages of being in good emotional health (49.5%). Also, they are unlikely to see their doctors when they are sick and their parents are not so supportive of their children seeking therapists.

Due to the model minority stereotype, heavy expectations are placed on Asian Americans which leads to negative psychological impact. Although they experience mental strain, Asian Americans avoid seeking and utilizing mental health services out of fear that just to acknowledge anything less than perfect mental health will bring shame to their family. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, non-Hispanic Asian U.S. adults with any mental illness have the lowest annual treatment rate, at 24.9%, compared to other racial demographic groups.

Unfortunately, some Asian Americans have become inhibited from advancing and succeeding in their roles due to severe mental pressure. This idea that Asian Americans are in better health than the general population and therefore do not need as much healthcare and mental resources is incredibly damaging and detrimental, to say the least.

Not Your Model Minority

The model minority myth continues to harm and invalidate the enduring hardships that Asian Americans face. Therefore, it’s vital to educate others about the dangers of perpetuating the myth and fellow Asian Americans must also resist the urge to buy into it. Based on the Cal Poly Pomona survey, Asian American millennials feel like they’re in a constant limbo because they are unsure of how to manage the expectations of their parents, as well as higher institutions, the workplace, and the outside world. This indicates that more attention, effort, and actions are needed to uplift and provide a platform for Asian Americans to utilize their voices more effectively.

Higher institutions can dispel the myth by not wrongfully assuming students are committed to STEM and medical fields and instead provide faculty and resources to help them explore their potential and capacities. While some students may be more academically successful than others, they are still in need of an educational support system and proper mentorship.

For managers in the workforce, it’s crucial to understand the structural and systemic racism that prevents Asian Americans from obtaining promotions or being employed. Addressing these racial discrepancies and developing better diversity programs that support Asian employees and lead to leadership positions is crucial.

Physical and mental health programs need to include culturally competent health professionals in order to cater specifically to the needs of Asian Americans. Ensuring that there is sufficient awareness of these programs in school systems and within organizations in the community may positively influence health-seeking behavior.

Too often do Asian American voices go unheard — it’s crucial to acknowledge their unique experiences which have allowed them to be resilient and persevere in a society filled with barriers. The narrative around Asian Americans needs to change and, collectively, people need to challenge and debunk the myth that continues to inflict lasting damage.

About the AATRI Generation Study

Millennials and Gen Zs (whom we call MilleniGenZs) were born in the early 1980s onward. Despite the volumes of research on these generations, there is minimal research on multicultural perspectives, especially Asian Americans. To correct this,Cal Poly Pomona’s Asian American Transnational Research Initiative(AATRI), with support from Intertrend Communications — a multicultural creative agency — started a longitudinal study evaluating the evolving attitudes and behaviors among our diverse youth population.

A survey was administered to nearly 1,000 MilleniGenZ students and graduates living in Southern California between January and June 2018. The survey included 184 questions in total around the topics of relationships, romance, political beliefs, social media participation, labor, and the future. We will continue surveying this population to track how their attitudes shift over time. AATRI is led by Dr. Mary Yu Danico (mkydanico@cpp.edu).